Divestment seems like such a crystal clear answer to the fossil fuel problem, but in real life, circumstances are a lot messier.

This has been a banner year for big-name university divestment from fossil fuels.

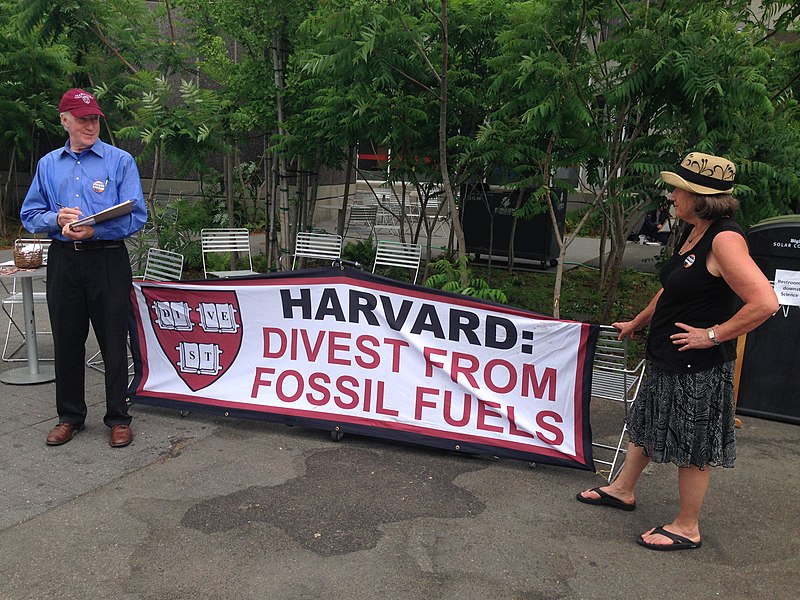

In March, Rutgers announced its intention to cease investing in fossil fuel companies, sell off its existing portfolio within a decade, and invest instead in renewables. Princeton followed in June with a plan to conditionally divest from thermal coal and tar sands investments, from companies pushing climate disinformation, and they further plan to make the rest of their vast endowment carbon neutral. Harvard bowed to years of student pressure in September, making public their intention to stop investing in companies that develop or explore for fossil fuel reserves, while their current investments in private equity firms with fossil fuel portfolios will sunset over time. And earlier this month, Dartmouth announced their own divestment initiative, planning no further direct investment and allowing current holdings to expire.

While the shift of massive, multi-billion dollar endowments away from funding the fossil fuel industry represents a victory for student activists and climate-minded petition-signers who want to change the world, it’s not clear that the world will be changed via divestment in quite the way they expect. Like many appealingly simple and morally clear solutions, fossil fuel divestment sounds better on paper, and the real world effects (in other words, the effects that matter) are, at best, dubious, and in some cases turn out rather opposite to the way the activists hope.

Consider: what does divestment mean, anyway? If a university sells off its ownership stake in a coal-burning power plant, they may no longer be responsible for the effects of that investment. The new owner, however, is, and that is seldom considered in the equation. In 2019, Engie SA, a French utility company, decided to go green, selling off their legacy coal plants. The buyer, Riverstone Holdings, an American private equity firm, didn’t shutter the plants, but instead used them to create a new, profitable venture in electricity generation. The plants still emit the same 5.1 metric tons of carbon per year into the atmosphere as they always did, but the French company that sold them can polish up their green marketing claims while absolutely nothing has changed for the planet.

The idea is that if everybody divests, the industry will be rendered socially toxic, a strategy which worked when the goal was ending apartheid in South Africa. However, South Africa’s exports are not nearly so popular as energy itself, and that was a different time when more people could agree that racism was, in fact, bad. Nowadays, try to cast shade on anything that people of conscience should agree is reprehensible (the Holocaust, say, or deliberately worsening and lengthening a pandemic), and someone will leap to defend it. Do we not expect that there will be firms, funds, or sufficiently monied Koch-like individuals ready to snap up these toxic properties, especially if a mass movement toward divestment saturates the market with cheap opportunities to make a buck? It’s already happening, and private firms don’t have to disclose as much about their dirty deeds.

Finally, there’s the possibility that California’s recent beach-killing oil spill was made worse by California’s transition to greener energy sources. Shifting investment away from oil while offshore rigs are still in production means less money for preventative maintenance and repair, and also encourages companies not to sink further funds into a doomed industry, both of which are circumstances that made it harder to find and fix the underwater leak before it became a much bigger problem than it had to be. If divestment is intended to strangle fossil fuel companies by starving them of financial resources, it may work, but we may not like how they break down as they die.

Divestment seems like such a crystal clear answer to the fossil fuel problem, but in real life, circumstances are a lot messier. This is never going to be solved by “one weird trick.” It’s going to take immense effort, the brightest imaginations (both living and not yet born), and uncomfortable sacrifices from institutions, businesses, governments, and yes, individuals like you and me. As long as someone is buying, someone else will find a way to sell these products, and most of the rich world is acting like the status quo is our birthright.

Related: Whose Fault is Climate Change?

Join the conversation!