Generics companies failed to scale back on opioid distribution even when orders were highly suspicious.

Douglas S. Boothe, the chief executive of Actavis, a generics manufacturer, was approached by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seven years ago and asked to cut production of oxycodone. Boothe “wasn’t interested and rejected the request that Actavis voluntarily cut its supply to U.S. pharmacies,” according to exhibits recently unsealed an opioid lawsuit. Now, Boothe and others from the generic drug industry are taking center stage.

The records show how generic pain pill makers fought to gain market share even as the addictive effects of opioids were known and how some of the manufacturers were warned by auditors or regulators that they were not meeting federal requirements for detecting suspicious high-volume orders. Boothe denied fault in his deposition and emphasized that Actavis could not control how its drugs eventually entered the market.

“Once it goes outside of our chain of custody, we have no capability or responsibility or accountability…Once we ship a valid order to a wholesaler or ship a valid order to a distributor…our chain of custody is finished at that point,” he said. The generic companies further said they “should not be held responsible for the actions of those who abused the drugs and that the DEA had all the information it needed to block pills from reaching the black market.”

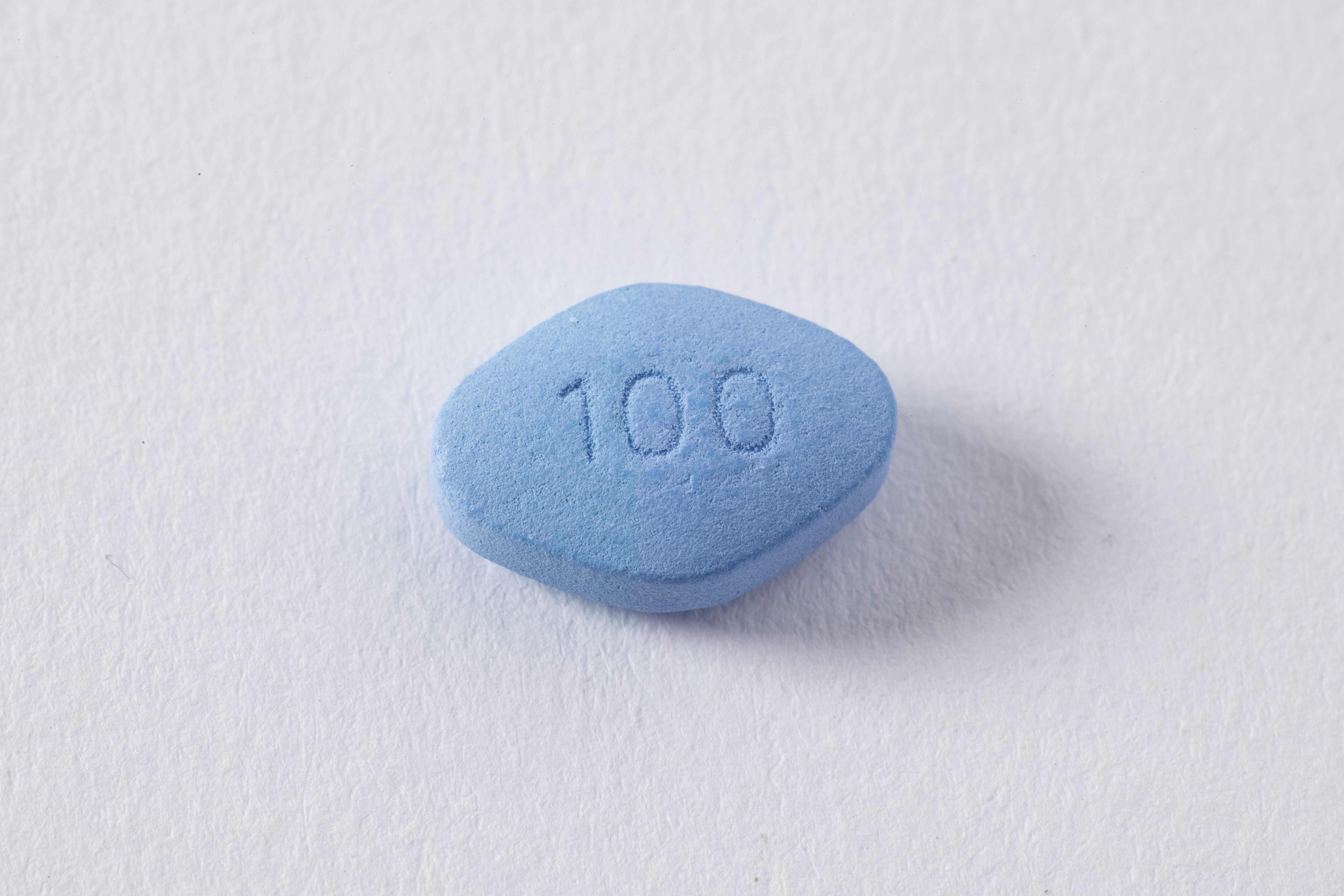

In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first generic versions of OxyContin, known as oxycodone hydrochloride. Among the early biddersi to win approval for a generic was Amide Pharmaceutical of Little Falls, N.J., with just 200 employees. Actavis, a European company, purchased Amide in 2005, stating it would give the small manufacturer an “important foothold in the US market…to generate significant opportunities to drive revenue growth.”

Actavis’s sales of the generic version of OxyContin and other drugs containing oxycodone grew from 559 million in 2006 to more than 1.1 billion in 2012, according to the DEA, and sales of hydrocodone increased from 2.2 billion to nearly 3 billion during that same period. But, because they were generics, the companies were able to increase the amount sold under the radar.

“We weren’t really a household name, none of us,” said Nancy Baran, Actavis’s former head of customer service. “Generics are not advertised on T.V. No one ever hears your name. I worked at the company for ten years, and my friends would still ask, ‘Where?’”

The companies also blamed the crisis on overprescribing by physicians and pharmacists in “pill mills.” The government tried going after physicians who were prescribing generics, too, but soon discover each case took months to get passed all the red tape.

“We kept trying to work our way back up the chain, to the source,” Barbara J. Boockholdt, former chief of the regulatory section for DEA’s Office of Diversion Control. In 2011, she visited the office that handles Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS ) and requested reports on the nation’s largest opioid manufacturers. She couldn’t believe it when she found the lesser known companies to have significant market share.

“I was shocked; I couldn’t believe it, Mallinckrodt was the biggest, and then there was Actavis,” Boockholdt said. “Everyone had been talking about Purdue, but they weren’t even close.”

Actavis’ Michael R. Clarke, the company’s vice president for ethics and compliance, testified in a deposition that it felt like DEA officials were treating Actavis like “street dealers.” Mallinckrodt and others, like Par, a company founded in the 1970s, were shocked that they were fingered. Par would later be acquired for $8 billion by Endo Pharmaceuticals.

If they were able to fly under the radar in the beginning, the good old days are definitely over. All of these companies with once-discrete operations have now been thrust into the spotlight.

Sources:

Little-known makers of generic drugs played central role in opioid crisis, records show

Join the conversation!