According to Ojibwe law, manoomin, or wild rice, has the right to exist, flourish, regenerate, and evolve. Now we’ll see if that right stands up in court.

According to the Ojibwe migration story, long ago, a prophet told them to move from their ancestral homeland on the Atlantic coast and to go west until they reached a land where food grew on the water. They did, and found a new home in the Great Lakes region where wild rice, or manoomin, grew in the shallow water of lakes and rivers.

Manoomin became a staple food for the Ojibwe people, the first solid food they feed their babies, and often the last food of the elders. It’s present in ceremonies, potluck meals, and part of the harvest can be sold to make a modest living. Gathering the grain as it ripens in the fall is a ritual that binds the community together, with people of all ages contributing to a successful harvest. In 2020, during the pandemic, more people were able to go ricing, a naturally safe and socially distanced activity that provided food and normalcy for people out of work and isolated by quarantines. Wild rice keeps the Ojibwe going and carries them through.

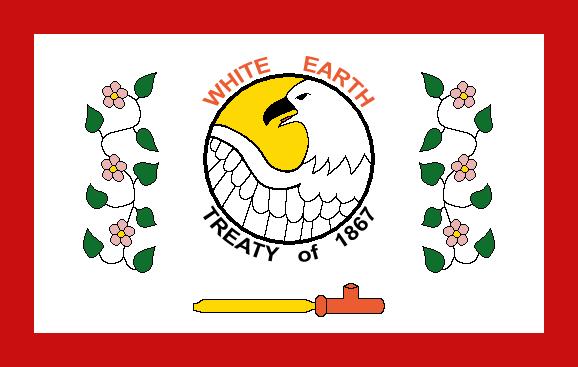

In 2018, recognizing its central role in their culture, the White Earth band of Ojibwe passed a law giving manoomin legal rights in order to protect the rice, the water it lives in, and to secure the existence of both for future generations. According to the law, “Manoomin, or wild rice, within all the Chippewa ceded territories, possesses inherent rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and evolve, as well as inherent rights to restoration, recovery, and preservation.” Further, the wild rice has “the right to clean water and freshwater habitat, the right to a natural environment free from industrial pollution, the right to a healthy, stable climate free from human-caused climate change impacts, the right to be free from patenting, the right to be free from contamination by genetically engineered organisms.”

Although the law is unusual, the first to bestow rights upon a plant species, it’s not unprecedented. Besides the Ojibwe, Bolivia, Ecuador, India, New Zealand, and the Ho-Chunk and Ponca Indigenous nations have recognized Rights of Nature to varying degrees, granting legal protections to features like rivers and glaciers. These are not simple property rights, of the sort that allow land owners to make decisions about the fate of their holdings, but instead grant a sort of personhood to parts of nature itself. Multiple treaties guarantee usufructory rights to Indigenous people in Minnesota; like a power of attorney document, they may give the Anishinaabe nation the right to act on behalf of manoomin in court.

Which, suddenly, has become important.

The state of Minnesota plans to allow Enbridge, a Canadian company, to divert five billion gallons of water for use in the construction of a new Line 3 pipeline, that would carry heavy tar sands oil from Canada, across upper Minnesota, to Wisconsin. The old pipeline dates from the 1960s and is in poor repair; Enbridge claims that it’s easier to build a new pipeline to carry an increased load than it is to keep fixing the old one.

The Ojibwe (along with other environmental groups and activists) say that not only can Enbridge not be trusted, with Line 3 having been responsible in 1991 for the largest inland oil spill in the country’s history, but that tar sands oil should stay in the ground instead of contributing to the climate crisis that is unfolding (and burning) all around us. The oil Enbridge wants to send through the new Line 3 is expected to cause $287 billion in environmental costs over the next 30 years, according to one review, while creating only about 20 permanent jobs.

Right now, though, the Ojibwe are seeking an injunction against the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to void Enbridge’s water permit, the first case of its kind in tribal court. Those five billion missing gallons of water threaten the manoomin, as well as the treaty rights of the Ojibwe people and their ability to gather rice, hunt, and fish that was guaranteed to them by the American government. It’s a deal their ancestors made with ours, to let immigrants settle on land that was once all theirs. Treaties, along with the Constitution, are the supreme law of the land. If the State of Minnesota or the United States doesn’t want to either observe treaties or renegotiate them, perhaps they ought to give the land back to the people willing to endure abuse to defend it.

Related: Lake Erie Bill of Rights Wins in Ohio

Join the conversation!