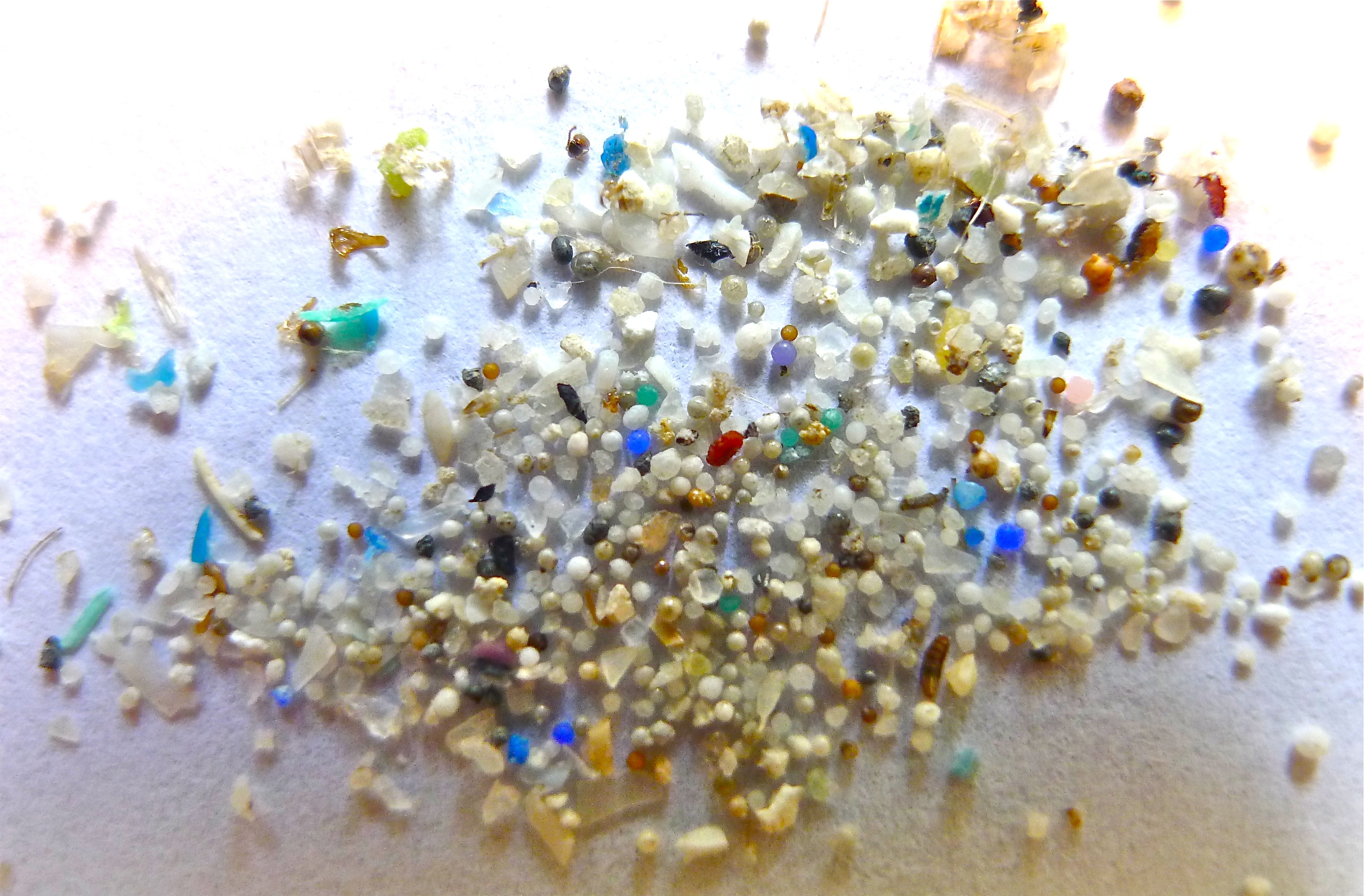

Microplastic pollution is everywhere, from the tallest mountain to the deepest sea to human guts, and we still don’t know all the effects it has.

Nearly ten billion metric tons of plastic have been made, used, and disposed of since the early 1900s, and not all of it ends up landfilled or recycled. We’ve known for years that tiny pieces of plastic get into our waterways, but now they’re turning up everywhere. Microplastic bits can be found all over the world, in places big and small, and unfortunately, they’re causing real problems.

Between December 2017 and January 2019, researchers from Cornell and Utah State University collected data related to the distribution of microplastic particles in the atmosphere over national parks and wild areas across the western United States. They identified the specific types of plastic that they found to figure out where they came from, and looked at the way they move through the air and where they eventually fall. Most were fibers from clothing and textiles. About a third were acrylic microbeads like those found in paint and industrial coatings. Some were tiny fragments from larger pieces of plastic. Results from the study suggest that over a thousand tons of legacy microplastic fall on protected lands in the American West each year, kicked up by traffic and blown in by ocean breeze. (Since researchers didn’t count particles that were clear or white, this is likely an underestimate.)

Microplastics become airborne so easily that they can be found even in surprisingly remote places. In the Arctic, Antarctic, the High Alps, and atop the remaining glaciers and ice sheets, microplastic shards (combined with particles of soot) make snow darker. Dark surfaces absorb the sun’s heat, rather than reflecting it, melting the ice beneath more quickly, contributing to a feedback loop of increasing warmth.

Researchers from the New Jersey Institute of Technology decided to examine what happens when two common microplastic particles, polyethylene and polystyrene, make their way into municipal sewer systems. It turns out that bacteria easily colonize the surfaces of these particles, forming biofilms in the sludge at wastewater treatment plants. These biofilms foster a multitude of bacteria in a kind of “meet and greet” situation where genes, including those for antibiotic resistance, can be traded like sportsball cards. After only three days, genes that provide resistance to sulfonamides, a common antibiotic, were 30 times more prevalent in sludge biofilms on microplastic surfaces as compared to the control group that used sand as the host surface.

Once the treatment plant extracts the sludge, where does it go? Often, farm fields. In 2019, a Kansas State University researcher investigated whether microplastic bits in sewage sludge would negatively affect crops. The result? Wheat plants grown with microplastics in the soil accumulated 1.5 times more toxic cadmium than those without. Incidentally, the microplastics also caused other problems, like preventing proper soil drainage, while concentrating pharmaceutical contaminants that easily soak into the plastic.

Since microplastics can be found from the highest mountain to the deepest sea, could they also be inside of us? They can – and they are. Not only do we inhale airborne particles which may accumulate in our lungs, they’re also in our organs. Researchers who obtained 47 samples of human lung, liver, spleen, and kidney tissue from a tissue bank found microplastic particles in every sample. Not enough research has been done to learn what the cumulative effect of a lifetime of living, breathing, and absorbing tiny shards of plastic could be, but it’s probably not good.

All of which may be why California is the first state attempting to develop guidelines concerning the acceptable level of microplastic contamination in drinking water. While the potential guidelines would lack the force of law, we should probably be concerned about consuming something that affects immune systems, heart health, and sperm counts in rodents. California water providers say it’s too early to make decisions like this (of course they would), but the truth is that it may already be too late. We created a world full of plastic dust. Now we must live in it.

Related: Just one word: Microplastics

Join the conversation!