What would not only make progress toward climate goals but also be a real reason for Thanksgiving? Land Back!

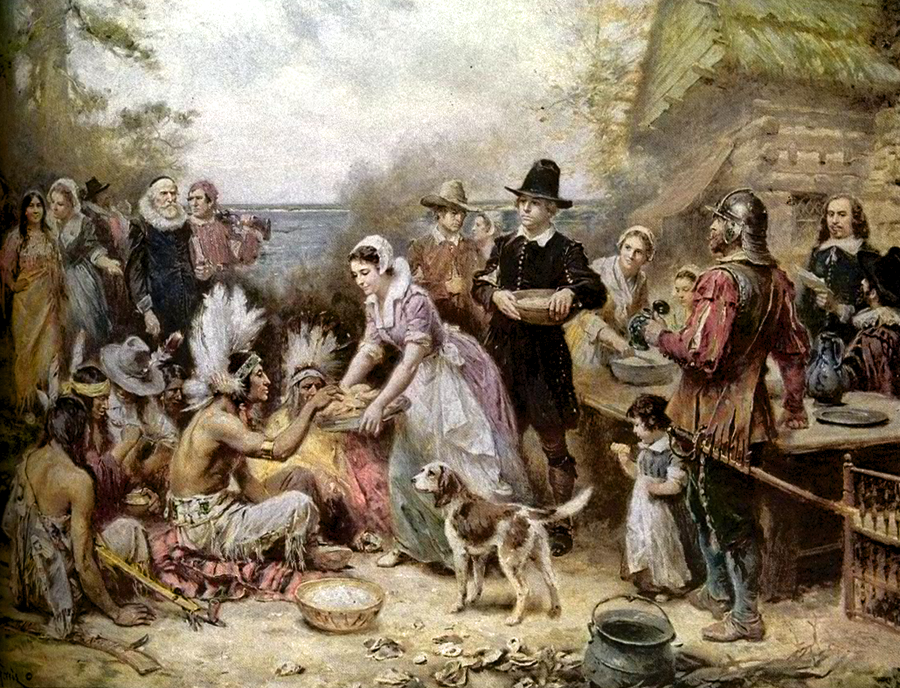

Ah, Thanksgiving! The opening volley of the annual Giftma$ season, when we gorge ourselves alongside family and friends (or not, since there’s still a pandemic going on) and argue politics with Uncle Tom, all to observe a mythic proto-American feast where Indigenous people provided starving settlers with abundant, lifesaving food and then disappeared in anticipation of Manifest Destiny, the Trail of Tears, rez commods and land acknowledgments.

While it’s true that robbing Wampanoag food caches saved the lives of Pilgrims who arrived too late in the year to plant crops, that Tisquantum, a Patuxet Wampanoag man who learned English after being kidnapped and taken to Europe, taught them how to plant herring with their stolen corn in order to fertilize the sandy soil, and that Governor Bradford called for a harvest festival the next year, the rest of the Thanksgiving story is pure American mythology and wishful thinking.

The Wampanoag people did not disappear; in fact, their children sit in schools today listening to a distorted, painful version of their own history. Pilgrims arrived in a land that was emptier than usual not because it was untouched and wild, but because so many of the original inhabitants were dead from a European disease like smallpox. Venison and seafood likely graced the table at the original (secular) feast in greater quantities than turkey. And Thanksgiving wouldn’t be an American holiday until President Lincoln declared it so in 1863, to foster unity not between Native Americans and the descendants of colonists, but between suffering and unruly factions in our Civil War. Perhaps that political argument with Uncle Tom in the MAGA hat is the most traditional part of the holiday, after all.

We gather around our Thanksgiving tables each year not long after the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference. The 2022 iteration, COP27, was held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, and the fact that we’ve now had 27 of these conferences tells you not only that they haven’t saved the world at numbers 1-26, but you shouldn’t expect too much from this one either.

This year’s COP(out)27 looked like a fossil fuel trade show, as a record number – 636! – of lobbyists and shills simping for the coal, oil and gas industries mingled with delegates from wealthy nations looking for the easiest way to duck the consequences of our collective actions while making as few changes to industrial culture as possible. In the grand tradition of people like this everywhere, they eventually promised to throw money at the problem.

But, how? The problem is way more complex than saying, “Sorry that your island nation disappeared or your crops were washed away by floods, kid, here’s $5, now go buy yourself something nice.” A third of the world’s capital is held by the United States, and a lot of that money is tied up in retirement accounts, wealth that will only be pried from cold, dead fingers. Yet, most of the need for that capital is in the Global South, which has long been raided for the sort of wealth that, well, grows businesses and retirement accounts in the U.S. and Europe while generating carbon levels that wreak havoc on the world’s poorest. What gives?

Wheelers and dealers at COP27 have a plan, though. Instead of redistributing cash from North American retirees to suffering Somalians and afflicted Afghanis, how about redirecting the investment potential of all that cash to development projects (like wind farms) in those countries instead, with the added bonus of generating a return on investment that enriches Uncle Tom’s portfolio, too? It sounds great, unless you know anything about debt, usury and history.

According to experts at the World Bank and people like John Kerry, the problem lies in making foreign investments just as safe as similar domestic projects. Unfortunately, countries that have been colonized, mined, and otherwise pillaged and their treasure carried off by powerful interests (that’s us) for generations tend to be (shockingly?) unstable, which would require the influx of significant public monies in order to guarantee the safety of Uncle Tom’s pension fund from the vicissitudes of local politics or even further climate disasters. What’s more, locking such nations into debt traps (where they are obligated to pay already-rich countries more interest than the project generates in revenue) is a fake solution that forces them into further poverty. We’ve seen this before and we know how it ends.

The one thing that might work is the thing rich countries are, of course, least willing to do.

Consider Kwesawe’k, a small island off of Price Edward’s Island, Canada. Its 210 acres of wetlands, marsh, forest and coastline, small mammals and shorebirds will be purchased by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and in five years, ownership will be transferred to the Mi’kmaw people, whose land this originally was.

Consider, too, the Bois Forte Ojibwe reservation in northeastern Minnesota. A century ago, the Federal government allotted some parcels of reservation land to the Ojibwe people, and then sold off the rest. Earlier this year, the nonprofit Conservation Fund repurchased over 28,000 acres of this “lost” reservation land from PotlatchDeltic, a timber company, and intends to return it to the Ojibwe in the largest Land Back agreement to date. It covers more than 20% of the original reservation land, and tribal members will be able to access it for hunting, fishing, and gathering food and medicine.

Then, consider Fones Cliff, ancestral land that is sacred to the Rappahannock Tribe of Virginia. Last August, the Chesapeake Conservancy purchased all 465 acres and donated the title to to the Rappahannock people. It will remain publicly accessible and the Tribe plans to use it for educational purposes for the public and for tribal youth.

Ever since the Wampanoag let the Pilgrims settle on Native land in exchange for a mutual protection pact, land has been transferred away by treaty, force, and trickery, out of the hands of those who fed themselves from its bounty for thousands of years, and into the hands of a culture that needed help feeding itself, but which would go on to cause the kind of climate damage that 27 worldwide conferences (so far) couldn’t fix.

Where Indigenous people regain the ability to manage their ancestral land, wonderful things have happened. Once land was demarcated for the Deni (an Amazonian people) and they were no longer constantly harassed by loggers, they brought the pirarucu fish back to the Xeruá river. Plains tribes reintroducing bison have been able to restore prairie ecosystems, improve food security and possibly mitigate climate change. A regenerative farm on Diné land in New Mexico is restoring fertile soil, connecting nature and decolonization while teaching others how to grow their own food in a healthy way.

Around the world, the LandBack movement has been growing. It certainly could (and maybe should) mean directly giving land back to Indigenous people and communities, but could also be as simple as paying annual “rent” to the people whose land we occupy, rewriting laws to let Indigenous communities exercise self-government, jurisdiction, and permitting rights over their territories, or providing housing for homeless Indigenous people. (No, you wouldn’t necessarily have to move.) The United States could even, finally, seat Kimberly Teehee, the Cherokee delegate whose place was promised two hundred years ago. Any concrete action or real change is more useful than simple land acknowledgments, which is why rich countries may be reluctant to take that step. However, if they do, it could be a hedge against some of the effects of climate change, and that would be a real cause for thanksgiving.

Related: Ponca Reclaim Land at Historic Crossing

Join the conversation!