Physicians Asked to be Perfect in an Imperfect World

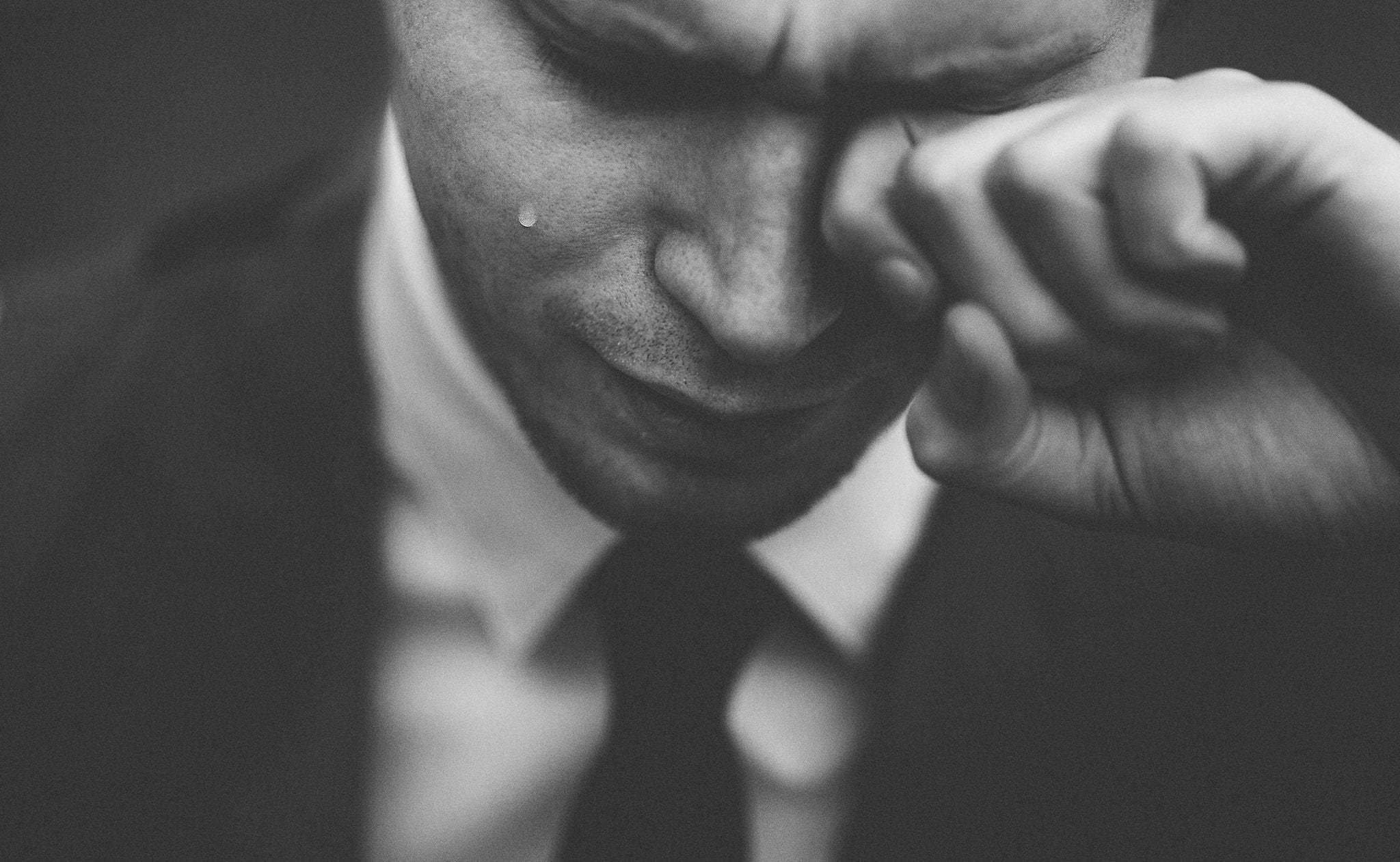

“Unlike a lot of other people whose identities aren’t as tied to their profession, a physician’s ego is deeply entwined with what they do and with the patients they serve,” emergency medicine physician Laurie Drill-Mellum said. “We are the only profession that is expected to bat 1000 every single day. Physicians are asked to be perfect in an imperfect world. There is no way a physician can practice medicine and not be a witness to, a cause of or a part of something going wrong at least once in their career. Even so, when that happens it just tears us up inside.”

She added, “Physicians think, ‘If I work hard enough, if I try hard enough, if I burn the candle at both ends, then I should be able to prevent mistakes. When something bad actually happens, it reflects on you, you’re falling short, you didn’t do that perfectly: No one wants that to happen.”

When a medical error is reported to Constellation, the Minneapolis-based collective of medical malpractice insurers, at which Drill-Mellum is the chief medical officer, the information is passed to a claim consultant who connects the clinician with a peer support doctor.

“We have a team which consists of four doctors that are experienced physician leaders,” Drill-Mellum said. “They’ve been trained in responding to situations where physicians or other clinicians are under stress. They are really good listeners. They’re there to support and normalize the feelings that people are having.”

Loie Lenarz, M.D., former medical director of clinician professional development for Fairview Health Services, is one of Constellation’s peer counselors. When the retired physician is given the name of a peer who needs support, Lenarz reaches out, offering a phone conversation or a personal meeting. Usually, after this first connection and the questions asked, she doesn’t hear back after. So, after a couple of weeks, she’ll reach out again.

“I’ll say, ‘I don’t mean to be a pest. But I want you to know that I’m available. Let me know when you’d like to talk, or if you don’t need to talk to me, you can tell me that, too.’ After that second contact, most call back,” she said, adding, “On that very first phone call, one of the things I talk to them about is the support resources they have available. In an open-ended way, I ask them if they feel like they have the support they need in their lives. I might say, ‘Your support could come from family or friends. It might be your faith community or seeing a counselor.” Then a question is asked, such as “Do you have what you need?’ Most people I talk to say they are glad we talked, that it helped them feel supported through this traumatic experience.”

When a patient has been hurt, this can be very damaging to a physician’s ego, Lenarz said. Doctors who have been sued are far more likely to be sued again over the next few years because they lose confidence. It’s something they dread to be asked about, but Lenarz knows it’s important to allow them to open up.

“One doctor I was working with said, ‘In spite of all I know about what happens to physicians in these situations and how we start to doubt our ability and over-order tests, it’s still happening to me. I can’t seem to make it not. I’m wondering if I should still be a doctor,’” Lenarz said. “This woman was smart and self-aware, but in spite of that she was still feeling that way. My job was to support her, to listen, to help her get past that roadblock so she could keep working.”

Lenarz understands that her own openness about her own imperfections and experiences helps the professionals she counsels. “I’ve witnessed the redemption that can occur when you directly address your past errors,” Lenarz said. “I try to explain that to the doctors I support.”

Sources:

Physicians, heal thyselves: Peer support reduces errors, improves practitioner mental health

Why doctors are leery about seeking mental health care for themselves

Join the conversation!