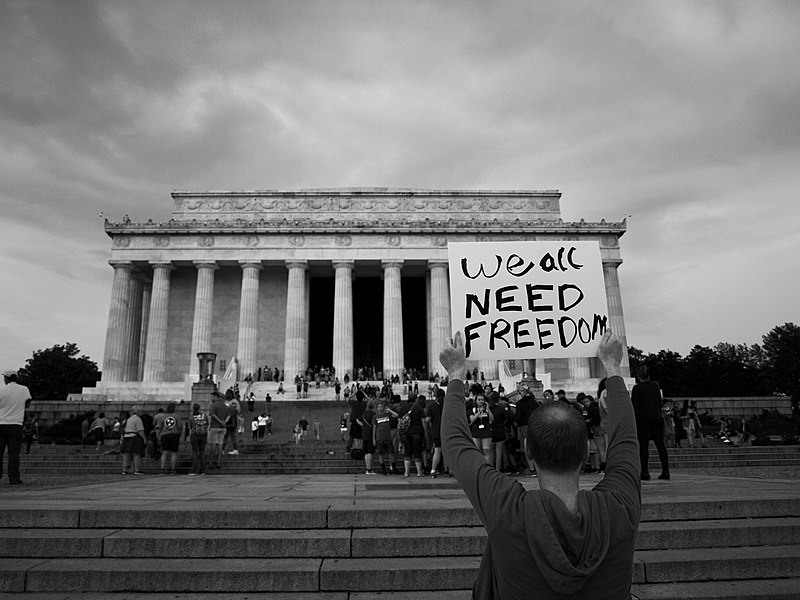

Freedom may seem like a simple thing to define, but it means different things to different people, and yours might be at odds with theirs.

Recently, my husband and I were visiting with one of our neighbors, sharing a smattering of history, politics and philosophy even as we share homegrown garlic and zucchini. We were comparing the American form of government to the British model, and our neighbor agreed to the familial resemblance, with the caveat that “we have freedom” here.

That was a real head-scratcher for me. I mean, the monarchy has lost a significant amount of influence over the Commonwealth’s body politic since the days of dumping tea in the harbor and taxation without representation. It’s a stretch to claim that the people of Great Britain suffer under the benighted rule of autocratic dictators, any more than we do across the pond. Does freedom mean something different to my neighbor than it does to me?

In recent decades, the culture war between American political factions has precipitated a growing chasm in the way we use language to express ideas. Take “family,” for example. Even as largely Democratically-aligned Americans have expanded the idea of family to embrace a diversity of people who voluntarily care for and associate with each other, such as same-sex couples and even the idea of “chosen” family altogether, the right wing has responded by narrowing their definition (usually to one Godly man as head of household, the one woman he married, and their obligatory children). Yet, each side holds that the other is “anti-family.”

Similarly, the word “freedom” has become a contentious front in the culture war, muddying the waters even further on a word that already means so much to so many.

Ask people what freedom means to them and you’ll get an array of answers, but one of the most common has the sense of being able to do and say what one pleases, without fear or coercion. Who wouldn’t want that? The devil, however, is in the details. There’s a wide gulf between “freedom to” (play your stereo at blast volume, for example) and “freedom from” (having to hear your neighbor’s loud, awful music at all hours). Consider economist Ronald Coase’s thought experiment about a farmer and a rancher with adjacent land. To keep the cows out of the corn, someone’s going to have to go through the trouble and expense of building a fence, but should that burden fall on the owner of the crops, or of the cattle? Either way, freedom for one creates a cost for the other.

Then there’s the “taxation is theft” contingent, who balk at having to pay even a modest cost to, say, fix the roads, and that if the potholes get too big, real freedom is everybody being able to decide for themselves which auto shop to visit, whether they’re certified technicians or the local shadetree mechanic. Contrast with those who would rather pay less, via taxes, to fix the roads for everyone, instead of enduring the downtime and expense of car repairs. Or even those not yet born, whose freedom is already foreclosed by our collective inability to kick our addiction to internal combustion engines. Some of the people can be free all the time (generally, our betters). All of the people can be free some of the time, usually when someone else is constrained, willingly or not. Absolute liberty for all people all the time? It’s not a thing that exists.

Even if freedom means “not having the government all up in our business,” how does that play out without one person’s liberating deregulation simply moving the cost to someone else? And how hypocritical is it for the party that prides itself on literally having “Freedom Caucuses” that are working hard to take legal marriage away from people they don’t like, prevent private businesses from providing certain benefits to employees, or even restraining a whole non-criminal class of people from crossing state borders?

One might retreat, then, to a populist position, seeking the most freedom for the most people by citing majority rule in a democracy as the closest realistic approach to perfection. It’s hard to find a faction currently in power which doesn’t support this concept, even if they’re not, strictly speaking, democratically inclined. Minority parties rightly object, reminding us that majority-rule democracy is two wolves and a lamb voting on the dinner menu. Or as some put it, “we’re not free until all of us are free.”

There’s a metaphor, attributed to Isaac Asimov (or perhaps Ivan Kasanov), about bathrooms. It goes like this: if you live by yourself, you can go to the bathroom anytime, and sit there as long as you want. However, if another person moves in with you, your “bathroom freedom” is limited. Live with a lot of people, and it’s even further diminished; before long, people will be banging on the door and there might have to be a bathroom schedule. The more people we have around us, the more we have to consider others in the equation.

Liberty can never be absolute. It’s not all about you or me, it’s also about those who aren’t free to go out in public because others are exercising their “freedom” to go maskless during a public health crisis. Are you free if getting sick means choosing between dying, begging strangers for money, or losing your home? Is it living without fear or coercion if fact-based reporting can be fatal, a popular vote can nullify your marriage, you’re more likely to be killed by police, or you can’t drink the water? How free are any of us, living through all these converging crises, anyway? Maybe freedom really is about having nothing left to lose.

However, what if we could reimagine a more mature definition of freedom, one that concentrates less on being able to have your way no matter how many other people are harmed, while protecting even unpopular minorities against the tyranny of the majority? That’s where the anarchists come in. Contrary to the hype, anarchism isn’t simply chaos. It’s the belief that reasonable people can organize themselves to meet their own needs and those of their community without resorting to top-down, coercive power structures and without being destroyed by the tolerance paradox. Sounds like a worthy goal to me.

Maintaining maximal freedom isn’t for the lazy. It takes active thinking, instead of outsourcing one’s conclusions to politicians, business leaders and other talking heads. It requires real commitment to the idea that even people we don’t like deserve the same treatment we want for ourselves. A fair amount of self-restraint, responsibility and rulemaking is necessary, in ways that may not feel like freedom. And it takes action to maintain a standard of living that allows all of us to move beyond immediate fear for our wellbeing and the chance that the power-hungry will take advantage of our natural needs. That’s a lot to ask. Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to sustain a truly free society, instead of the one we have.

Related: The Social Cost of Freedom, Part 1 and Part 2

Join the conversation!