Officials in two Arizona counties confirmed the presence of plague-infected fleas around the small town of Taylor.

The Public Health departments of Navajo and Coconino counties sifted through countless burrows in search of the potentially plague-ridden pests.

Samples were collected from a handful of private properties scattered around the outskirts of town before being sent away for analysis.

Last week, the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute at the University of Arizona announced their findings – a number of local fleas are carrying Yersinia pestis.

The small, anaerobic bacteria has a history unlike any other, having tormented humanity from its earliest beginnings.

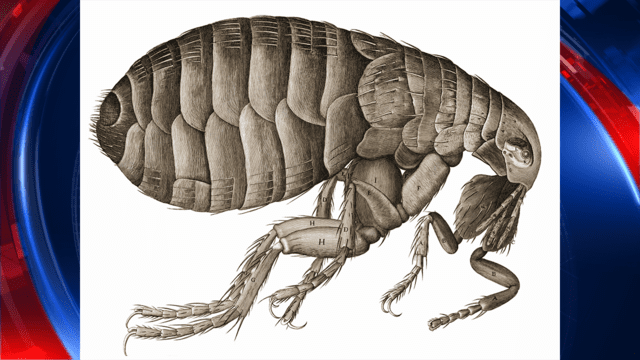

Spread by contact with fleas, rats, and a variety of small rodents, Y. pestis is best known for causing the condition known as the Bubonic Plague. Most modern-day historians claim the bacteria was responsible for the Black Death, which traveled down the Silk Road and through seaports to ravage much of Asia and medieval Europe.

Over the course of a single short decade in the 14th Century, Europe lost anywhere between thirty and sixty percent of its population to Y. pestis.

Outbreaks of plague continued to kill people around the world for another five-hundred years.

The advent of modern medicine and a popular awareness of how pathogens are transmitted led the threat from Y. pestis to decline from the late 19th century onward.

Nevertheless, several thousand cases of plague are reported around the globe each year.

While the presence of plague-infected fleas in Arizona may raise fears about another epidemic, the finding isn’t necessarily indicative of the disease’s impending comeback.

Each year, a handful of extraordinarily unlucky Americans are stricken with the Bubonic Plague. Most reported cases come from the West, with the brunt of incidents stemming from states like Arizona and New Mexico.

Anywhere between one and 17 people in the United States catch the sickness in any given year.

Although medieval encounters with Y. pestis often proved fatal, physicians stress that cases which receive prompt treatment tend to end with a happy prognosis. Antibiotics usually yield positive results when applied to combat the plague, but everyone displaying symptoms of infection should seek immediate medical help.

In late June, NPR spoke with Paul Ettestad, a public health veterinarian working for the New Mexico state health department.

Ettestad explained how animals tend to suffer the effects of plague far more than people – when fleas pick up Y. pestis and latch onto rats, cats, pups or prairie dogs, the consequences for mammalian communities can be devastating.

If a single prairie dog colony is affected, for instance, the bacterium amplifies.

“It’s like putting a match to a grass prairie,” Ettestad said. “Whoosh.”

NPR also distinguished between the varieties of plague caused by Y. pestis.

When people are bitten by infected fleas, they usually develop the bubonic derivation of the disease, which is characterized by hard, painful lumps called ‘buboes,’ which give the illness its name.

Within the buboes – often located on lymph nodes, legs, and inside armpits – the bacteria multiply.

The multiplication can cause Y. pestis to enter its victim’s bloodstream, transforming into the even-more serious septicemic plague. If left untreated, it may eventually spread to a person’s lungs, leading to pneumonic plague, which, NPR reports, is considered by the World Health Organization to be among the world’s most deadly infectious diseases.

One of the three cases of plague seen in New Mexico this year was pneumonic; the patient was, as of June, recovering at home from organ damage caused by the illness.

Ettestad said the infection probably started out as bubonic or septicemic but spread to the patient’s lungs because they didn’t seek medical treatment quickly enough.

“Sometimes people think they can tough it out at home and they’re gonna get better,” he explained. “What happens with the plague is you kinda hang on, hang on, hang on and then suddenly the bacteria can spread into your bloodstream extremely quickly and it can overwhelm a person.”

As a response to the latest outbreak in Arizona, public health officials said they’d notified residents who had plague-bearing fleas on their property, and promised to quickly treat the at-risk burrows.

Sources

Fleas test positive for the Plague in Coconino, Navajo Counties

Human Plague Cases Increasing In Southwest

The Plague Is Back, This Time In New Mexico

Join the conversation!