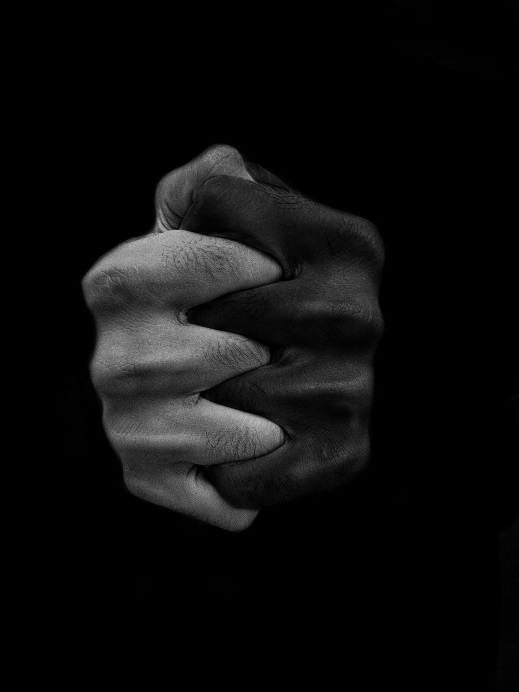

Black communities are being plagued by drug overdoses, especially fentanyl fatalities.

The largest spike in fentanyl overdoses in the state of Virginia has been seen in its Black population. Since 2018, the state has witnessed opioid overdose deaths among Black Virginians more than triple, according to date from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’ death certificate database. And the spike has been mostly centered around in Richmond.

Darryl Cousins, a Black counselor at several recovery houses for Virginians, said he’s lost three friends to overdoses in the past two months.

“You get three or four deaths, maybe in a week now, in Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield, instead of one or two a month,” Cousins said. “There’s not that much light being shed on the situation. It desensitizes you to death. All of a sudden it’s in every drug being sold. Fentanyl has taken over the drug world.”

Fentanyl, originally developed solely for use among cancer patients in chronic pain, is a synthetic opioid that is up to 100 times more powerful than morphine. It continues to flood into the U.S. at alarming rates, mostly from Mexico and China. The opioid offers a more potent offshoot of the same full-body euphoric sensation that heroin does. It also depresses breathing to dangerously low levels, which is why overdose fatalities are common.

“This explains why fentanyl is so deadly: It stops people’s breathing before they even realize it,” said Dr. Patrick L. Purdon, senior author of a study on the lethal nature of fentanyl center around Massachusetts General Hospital and published in August. In fact, three-quarters of fatal overdoses in Virginia have been linked to the synthetic.

Fentanyl is not only sold illicitly as a standalone drug. It is commonly mixed in with others, increasing its lethality. Drug dealers use fentanyl to “cut” heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine because it is cheap, and they don’t care about the end result – an ever-increasing overdose rate. Sometimes the cocktail is known to a buyer and sometimes its not.

“What’s also frightening is how the drug is being sought out,” Cousins said of fentanyl-laced heroin being used among Virginians. “I was trying to get a grip on it…I was trying to understand, why would you go looking for something that literally takes you to the brink of death?”

Tisha Wiley, a researcher with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said the opioid crisis in the Black community is one riddled with historical racism. As white patients easily got their hands on prescribed drugs like OxyContin in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Black patients found it much harder to convince doctors of high pain levels.

“One of the things that we hypothesized early in the pandemic was that Black patients were less likely to get prescribed pain medications, which would translate into Black patients having a harder time getting prescribed medications for opioid use disorder,” Wiley said. “That comes down to implicit bias. The bias also appears when Black people with addiction seek medically assisted treatment (MAT) for addiction, such as drugs like methadone, an FDA-approved opioid used to taper down cravings. And while white people with addiction are more likely to get diverted into treatment, such as rehab, Black and Hispanic people with addiction are more likely to be arrested.”

Jimmy Christmas, a Black licensed therapist with Richmond-based Riverside City Counseling, which offers substance abuse and mental health services, said, “When I look at what the white community has had access to, this physical apparatus of recovery homes, compared to the Black population, it makes me sad to even look at that. I’m sitting here and watching our country fail. For 20 or 30 years in the white community, there have been white families willing to pay for their loved ones’ treatment. I would like to believe that there is a pocket in the Black community that is willing and capable to pay for their treatment, too.”

Until this can happen, fentanyl will continue to plague Black Virginians, leading to more and more overdoses.

Sources:

Data Access – National Death Index

Black opioid overdose deaths in Virginia nearly tripled during pandemic

Overdose death rates increased significantly for Black, American Indian/Alaska Native people in 2020

Join the conversation!