Friday, Cassini died in a blaze of glory, leaving us a little more isolated in the universe. With no replacement (and science on the rocks), what’s next?

In 1982, Commodore International launched its bestselling Commodore 64 home computer, we all watched E.T. phone home, and Barney Clark became the first human recipient of a permanent artificial heart (or as permanent as 112 days can be). Also in 1982, the European Science Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences in America began talking about a joint venture to collaborate on future space missions. This partnership bore fruit in the form of the Cassini Saturn orbiter and the Huygens Titan probe. Despite the threat of budget cuts in the 1990s and used at times as a political football, the joint Saturn mission launched in October of 1997 and provided some of the most interesting discoveries to date from the outer solar system. Cassini, nearly out of fuel after 20 years in space, went out in a blaze of glory last Friday as the mission team guided their beloved craft into Saturn’s atmosphere.

As a joint effort involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Italian Space Agency (ASI), the mission is a shining example of the best kind of international collaboration. Teams from 17 countries worked together to design, launch, support, and provide scientific instruments for Cassini-Huygens. Radio receivers in California, Australia and Madrid handed off to each other around the clock for years as the Earth’s orbit brought each station across the horizon. $3.9 billion and the labor of over 5,000 people have gone into making the Cassini mission a success.

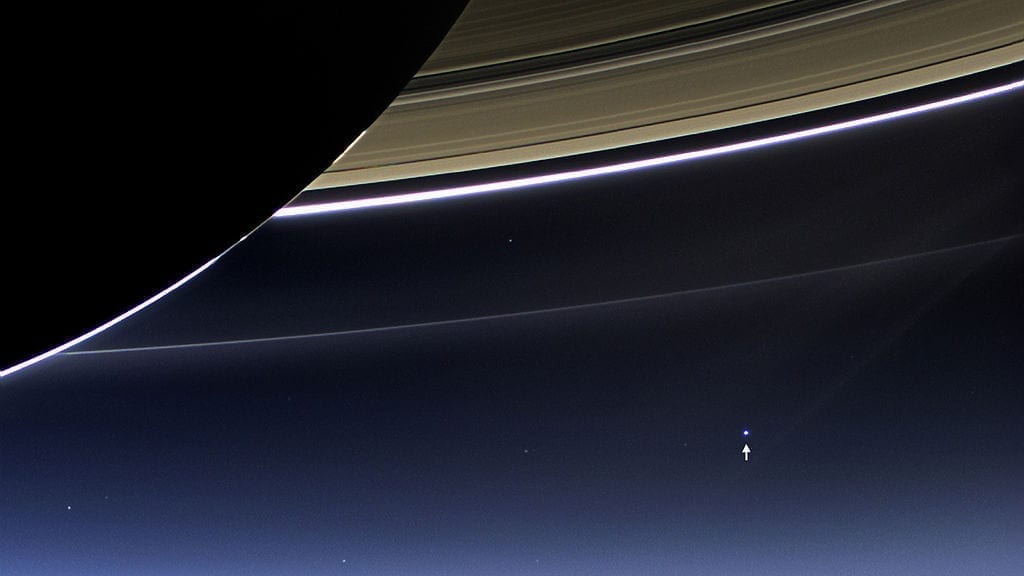

Cassini is also responsible for some of the best space science ever produced by humans. Thanks to this project, we now know that Saturn has not thousands of rings, but millions. New moons were discovered. We saw the first complete images of Saturn’s polar hexagon. Dropping the Huygens probe on Titan resulted in the first landing on another world on the far side of the asteroid belt. And we learned that the tiny moon Enceladus, thought to be a shiny iceball, was venting liquid water into space from jets at its south pole.

It’s precisely because of moons like Enceladus and Titan that the Cassini probe had to make its last, suicidal dive. Because these moons have the ingredients for life (organic materials, liquids, and a heat source), good sense and an international treaty prevented NASA from parking the probe in permanent orbit around Saturn, where it could one day crash into a potentially life-bearing moon and contaminate it with radioactive pollution or Earthly microbes.

The discoveries made by this amazing scientific machine have made Saturn a tempting target for future missions, but will they ever get off the ground? The outer solar system is an emptier, lonely place without Cassini. Juno, the probe launched in 2011 to visit Jupiter, is slated for a similar demise in the giant planet’s atmosphere next year. New Horizons, the plucky traveler that brought us images from Pluto in 2015, is off to explore the Kuiper belt and then leave our solar neighborhood. Voyager 1 and 2, launched in the 1970s, still whisper to us with half the wattage of a refrigerator lightbulb. It takes over 30 hours to send a signal and hear a reply, and by 2025 the Voyagers will be too weak to whisper at all.

There are grand plans on the drawing board, of course. In 2018, NASA plans to send probes to explore Martian geography and the Sun’s corona, and the European Space Agency is cooking up plans for Jupiter in the 2020s.

However, on Earth, times are changing. We no longer seem to be the science-forward species we once were. Systemic economic changes that drive outsourcing and automation also erode the tax base, and the scientific missions driven by the sheer joy of knowledge and exploration, made possible by our temporary oil-based prosperity in the Sixties and beyond, may not be possible in an era of budget cuts and resource depletion. Science has also given itself a bit of a black eye, as recent scandals involving dietary sugar and pay-to-play publishing can attest. Ideological and cultural movements that reject science, such as anti-vaccination sentiment and climate denial, signal that we won’t necessarily believe a scientific consensus if it calls cherished beliefs into question, and empowered religious fundamentalism is never going to be friendly to science. In these circumstances, dedicating public funds to scientific research is a challenge (although who knows, maybe we’ll outsource our science to third-world sweatshops, too). Any scientific efforts that remain afloat seem likelier to boost corporate profitability than to advance the human quest for knowledge, such as making “smart” cotton clothing that can harvest even more of our personal data.

So good night, fair Cassini. As you blazed across the Saturnian sky, you marked the beginning of the end of an exciting time. As we work our way through the remaining vapors of cheap petrochemical energy, and begin asking how we’ll live in a changing world without so much of it, our space presence will shrink, and one day grandparents will tell the little ones how it was when we reached out and touched the stars.

Join the conversation!