Last week’s global climate strikes exuded passion, but could other strikers show them how to claim their power more effectively?

Every day, there’s some new thing going wrong with the world. Workers are exploited, inequality is growing, birds are dying, the climate crisis is unfolding faster than expected, and the Amazon is (still) burning. Feeling powerless in the face of it all is understandable. However, there’s a certain kind of power that comes from having nothing left to lose. If you can convince enough people to join you, you can go on strike. Strikes are coming back into fashion nowadays, but will they be effective enough to save the world?

According to Melanie Simms and Alfred Crossman, two UK economics professors, strikes can work, but it depends upon which side has the most power and is best able to leverage it. Strikes, like protests, are a traditional way to express outrage over working conditions or political (in)action, but they’re of little practical use unless they achieve some form of lasting change. To do so, they must be able to credibly threaten the powers that be. For strikers, this is usually the ability and willingness to harm the economic standing of the owners of capital, whether through lost revenue or direct action. For political action, the threat in a democratic system is voting the bums out, and electing new, more favorable bums, although various historical revolutions hint at other options for defeating systemically entrenched opposition.

There are a number of ongoing and recent strikes to consider.

In mid-July, Blackjewel, a two-year old coal mining company, declared bankruptcy. Over a thousand miners received short notice that they’d soon be unemployed. However, as the company tried to discreetly ship out one last trainload of coal late one night, workers realized they had a final chance to try collecting thousands of dollars worth of unpaid wages, so they set up a blockade on the train tracks. Months later, the miners are still there, and the camp has become a focus for strikers and activists. Despite the grand promises he made to save coal country, Trump’s typically Twittery thumbs have remained silent about the strikers, while the Bernie Sanders campaign supplied them with pizza. It remains to be seen whether the coal workers will have their payday, or whether Blackjewel will prevail in this historically union-hostile region.

Medical workers are also taking part in strikes across the country. Friday morning, 2,200 nurses went on strike at the University of Chicago Medical Center, demanding safe staffing levels for patient care. Although the nurses have a great deal of leverage, with U of C moving patients to other hospitals and sending ambulances away, the one-day strike has been turned into a lockout. The hospital hired hundreds of temporary replacement nurses, and is also painting the striking nurses as hypocrites who claim they care about staffing levels yet refused to work, even to care for critically ill newborns. Several other medical worker unions are planning strikes in coming days, including 65,000 Kaiser Permanente workers in four states.

The General Motors strike might be the one that looms largest in the public eye. Over 46,000 autoworkers walked off the job a week ago, and they’re up against one of the most powerful corporations in the world. When a 2% wage increase wasn’t enough to satisfy striking workers, GM foisted the cost of workers’ health insurance onto the union. With the strike costing the company an estimated $50-$100 million per day, the UAW has some leverage, but workers’ resources are limited. This is an important moment in the class struggle, deciding whether workers stick together or continue to divide themselves in ways that are politically convenient for the owner class. Watch to see whether the Democrats learn to embrace the working class in Trump country by offering more policy than pizza, or whether they continue to emphasize identity politics over class struggle.

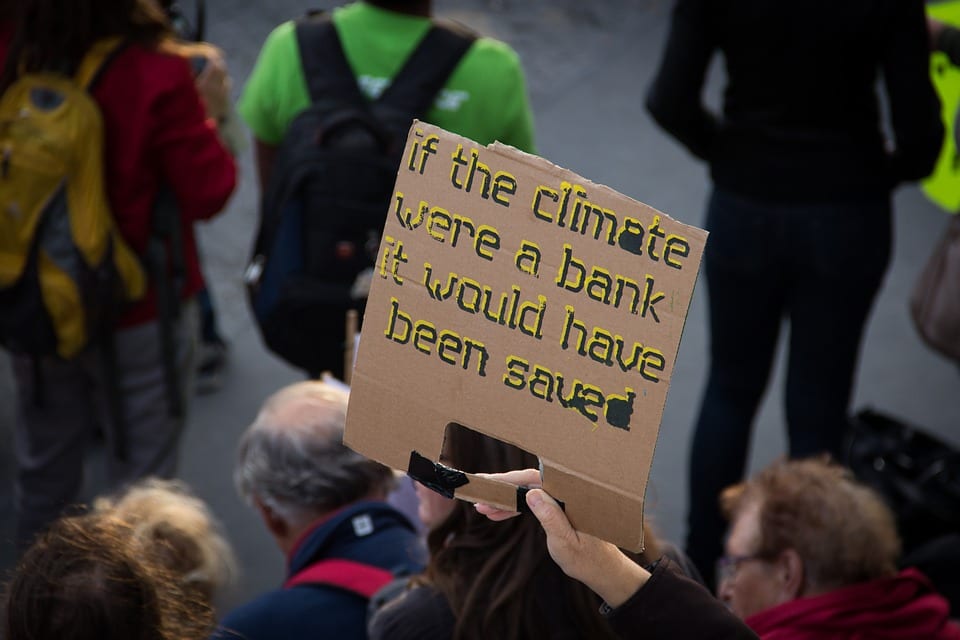

Which brings us, finally, to the recent worldwide climate strikes. Unlike coal miners, nurses, and autoworkers, the climate strikers have little leverage, yet their cause is the most important struggle going nowadays. Greta Thunberg’s skolstrejk för klimatet is an understandable action for young people who have clear vision yet lack agency. Even so, (some) school districts from New York to Oregon controlled and channeled students’ energy by excusing the absences and turning it into just another lesson plan. An estimated four million people took part worldwide, likely making it the largest climate protest in history, which sounds big until you realize it was just over 0.0005% of the world’s population, much smaller than the already marginal 3.5% that some say it takes to change the world through civil disobedience.

Remember, to be considered “peaceful,” one must have, and reject, the option of violence. Without the sort of credible threat (whether economic, political, or worse) that makes strikes and protests effective, they’re not peaceful, they’re merely harmless, and can be safely ignored by the powers that be. One wonders if those who advocate for unilateral civilian disarmament have considered this. Add in the fact that changing our way of life to a degree that would effectively stave off the worst of the climate crisis runs counter to the shorter-term interests of industry, workers, and consumers of all kinds, and the outlook for the climate strikers turns cloudy indeed. Hopefully they can find their power before it is too late.

Related: If Protesting Fails, Then What Do We Do?

Join the conversation!