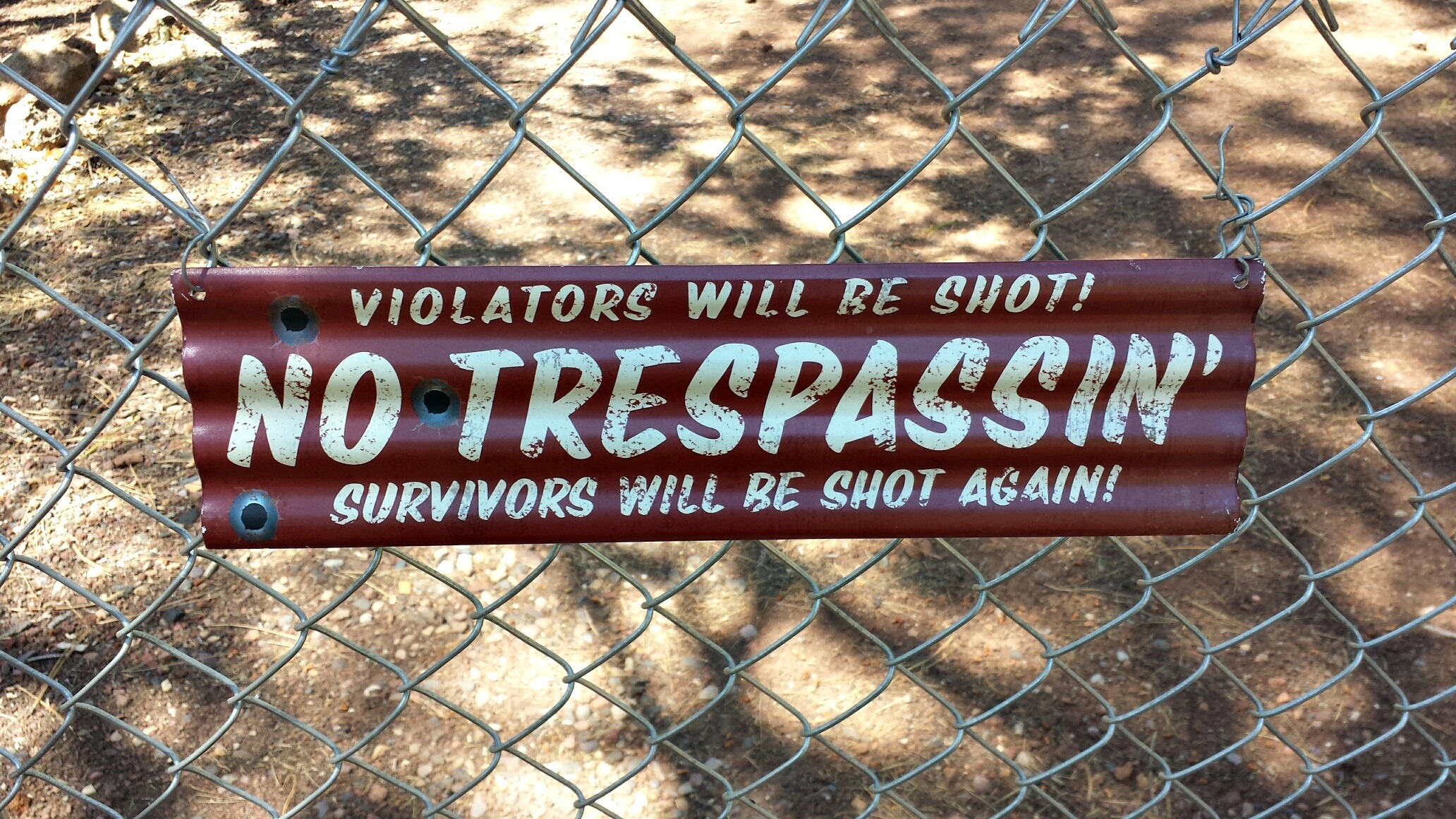

America’s story is full of ideas about what land rights should be. It’s not only private property and No Trespassing signs, so explore and find out!

Property and land rights are often taken for granted in the United States. After all, isn’t buying your own quarter-acre of paradise surrounded by a picket fence part of the American dream, and don’t you dare tread on me? Yes… and no. That’s one way of looking at land rights, but dig just a little deeper and there’s so much more to find.

If there’s a poster child for the American Dream, it would have to be Bill Gates. Far, now, from the Albuquerque garage where Microsoft was born, Gates decided to diversify his portfolio by investing in massive amounts of land. As of January 2021, Gates and his wife own 268,984 acres of American soil, 242,000 of which are farmland, more than anyone else in the United States. Gates, who could end world hunger and still be ridiculously wealthy, has donated funds to support smallholder farming. One wonders, however, if owning the land rights, instead of having to pay rent to a multibillionaire for all those acres, would help a cash-poor, land-poor generation of new farmers and do more to support smallholding in the long run.

Gates might own vast swaths of land, but he is unlikely to know every tree and hollow on it as well as the original inhabitants did. There’s another way to think of land rights, which is less about who owns a paper title to it, and more about who has stewarded those rivers and hills since time immemorial. Long displaced, Indigenous people are still fighting to regain stolen land, and a new generation is listening. Late last year, the Nez Perce tribe was able to purchase 148 acres of ancestral land in eastern Oregon that the U.S. Army removed them from in 1877. No longer considered trespassers, the tribe hopes to reintroduce sockeye salmon in the river their ancestors fished. “The very ground we walk on is made up of our ancestors. That’s how deep our connection is,” Nakia Williamson-Cloud told Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Trespassing used to be unthinkable in Montana, and not because wanderers turned back at the sight of a closed gate. One of the common land rights that eroded away so long ago that we barely know what we’ve lost is the right to roam, to wander others’ private property as easily as one would use a sidewalk. Once considered such a basic right that a Constitutional amendment guaranteeing it was believed unnecessary, the erosion of this freedom began after the Civil War, to prevent formerly enslaved people from hunting, foraging, or merely existing on land owned by white people. In wild Montana, however, would-be wanderers are only now losing this ground to newcomers who buy land and post “No Trespassing” signs, ignorant of the local culture. Locals are resisting, though, because to them, being fenced out of private property is like being slowly caged.

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, to Thomas Paine. Paine, oddly resuscitated as a hero by the likes of Glenn Beck, had some ideas that would make the right wing wince if they read his works.

Paine, for example, argued that nature and its bounty was “the common property of the human race.” Private property could be justified because the fruits of its cultivation should belong to the cultivator, but those who were excluded from such property did not forfeit their land rights, and were in fact due compensation. To accomplish this, Paine favored a “ground rent,” paid to the community by those who held private land. The proceeds would then be distributed as a lump-sum cash grant to every person when they reach adulthood, to be used for the procurement of some means of production, “to prevent their becoming poor.” It’s hard to see how the Glenn Beck crowd would interpret that as anything but Marxism, but here we are.

In the light of Thomas Paine’s argument that nature’s bounty belongs to all of us, of the right to roam that was once inherent to all before racism spurred the enforcement of private property, and the idea that people and the land they inhabit for generations share an intimate connection that they’re fighting to reclaim, it may become harder for a person of good conscience to hold to the idea that someone like Bill Gates should be able to own over 420 square miles of land as others struggle to feed themselves or find a place to live. Perhaps one day, more Americans will realize that it’s not a shadowy cabal of deep state satanic cannibal pedophiles keeping them down. It’s not even close.

Related: Land Use and Abuse, Rights and Wrongs

Join the conversation!