What’s behind a volatile situation brewing in Nova Scotia, where commercial fishermen and police are at odds with First Nations pursuing the right to a moderate livelihood?

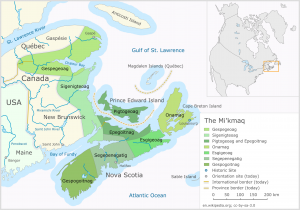

In 1752, the British governor of Nova Scotia, Canada, signed a treaty with the Mi’kmaq, which agreed that the Mi’kmaq “shall not be hindered from, but have free liberty of Hunting & Fishing as usual.” That right was codified in the Canadian Constitution and has been recognized and upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada. In 1999, the Court released the Marshall Decision which created the concept of “moderate livelihood,” allowing the Mi’kmaq to make a modest living (but not to grow rich, or compete with Westerners) in addition to harvesting resources for “food, social, and ceremonial purposes.”

The Court, however, has never explicitly defined what a moderate livelihood is. Is it up to the Mi’kmaq, as a sovereign nation on unceded territory, to decide what that means for their citizens, or is it regulated by the Canadian government? The slow-burning dispute between Canada’s First Nations and the descendants of colonial settlers has erupted anew in recent months, occasionally bursting into literal flames. It’s a moral and economic struggle that matters not only to Canadian industry, but to the future of the “civilized” world.

So, what’s the situation?

Last September, the Sipekne’katik First Nation decided to pursue a moderate livelihood by issuing 11 licenses to Indigenous fishermen hoping to trap lobster, in accordance with their treaty rights. Blowback from the local commercial fishing industry was swift and intense, from racist slurs and allegations of sabotaged traps to vandalism, theft and arson, as a lobster pound storing the Mi’kmaw catch burnt to the ground under “suspicious circumstances.” Police are accused of standing by and letting it all happen.

Ostensibly, the conflict hinges on responsible conservation practices. Commercial lobster fisheries object to off-season fishing by Indigenous groups, afraid that such exploitation will cause lobster numbers to plummet, killing the industry. It’s not a completely unwarranted fear, since fishing during molting season means that the egg-bearing females or undersized lobsters thrown back are likelier to die without a protective shell. Further south, however, Maine’s year-round season hasn’t overtaxed the stocks. Even more relevant is the relative size of the moderate livelihood fleet, with five or ten boats and a total of 250-500 traps, compared to the commercial fleet with 100 vessels allowed to deploy 35,000 traps in St. Mary’s Bay. Who is the real threat to sustainability here?

The Mi’kmaq are exploring multiple paths forward through this volatile situation. Chief Mike Sack of the Sipekne’katik First Nation plans to take legal action against commercial fishermen, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the RCMP, and some businesses, as well as filing human rights complaints. Meanwhile, leaders of the Membertou and Miawpukek First Nations teamed up with the Vancouver-based Premium Brands Holdings Corporation to purchase a 50% interest in Clearwater Seafoods, one of the largest seafood companies in North America. The Mi’kmaq will control the company’s fishing licenses, allowing them to harvest from a much larger share of Nova Scotia’s offshore territory, and they plan to hire more Indigenous people into the company.

Whether Canada’s First Nations defend their inherent and treaty rights to subsistence fishing, pursue legal challenges, or purchase commercial fishing fleets outright, one fact is clear. Native management over thousands of years did not ruin North America’s resource base over the long term. It took over-exploitation by colonial powers to do so to such a degree that limits and seasons had to be imposed so that people would know when to stop for a while and let the natural world recover. Perhaps we’d have a longer future ahead if all of us, not just the Mi’kmaq, sought to make a moderate livelihood from the resources we find around us, instead of aiming for the accumulation of wealth beyond need and reason. The right to sustenance must come before the opportunity to profit.

Related: Wet’suwet’en Solidarity Movement Growing

Sources:

The Facts Behind Mi’kmaw Fishing Rights

Inside Canada’s decades-long lobster feud

Nova Scotia lobster dispute: Mi’kmaw fishery isn’t a threat to conservation, say scientists

‘We won’: Indigenous group in Canada scoops up billion dollar seafood firm

Mi’kmaw First Nation planning ‘hundreds’ of legal suits amid opposition to fishery

Join the conversation!