Roselyn Tso, Diné (Navajo) nation member and Biden’s pick to lead the Indian Health Service, was confirmed by the Senate. She has a big challenge ahead.

Last Wednesday, the Senate finally confirmed Roselyn Tso by a unanimous voice vote to a four-year position as director of the Indian Health Service. Tso was nominated in March. The department has lacked a full-time leader for six of the last seven years. Tso takes the reins from Acting Director Elizabeth A. Fowler, a member of the Numinu (Comanche) nation. The last permanent director was Michael Weahkee, A:Shiwi (Pueblo of Zuni), who served less than a year under former President Trump.

Roselyn Tso has nearly forty years of experience working for the Indian Health Service, having started her career there in 1984 as an administrative officer in Yakama, Washington. After holding a series of positions with increasing responsibility, she served as the director leading the IHS’s operations for her own Diné (Navajo) Nation.

The last few years have been hard for the IHS, as the COVID pandemic disproportionately affected Native Americans and Alaskan Natives. Between 2019 and 2021, life expectancy for Indigenous Americans fell by more than six years to age 65, compared to the United States average of 76. Crowded living conditions, poverty, food insecurity, and little access to even chronically underfunded medical facilities made COVID especially deadly for people living on reservations. For one sample group of Native Americans, the mortality rate was 2.8 times higher than for the white sample group, even after adjusting for age. Native Americans also experienced higher mortality rates than Latino and African American groups, even with better vaccination rates.

Although a complete study of COVID’s effect on Native Americans can’t be completed until the virus has burned itself out (and the way we’re behaving, it may never do that), it’s safe to assume that starving the IHS of proper funding isn’t a great way for the government to uphold treaties, court decisions, and executive orders that promise to provide health care for Indigenous people and their sovereign nations. Native Americans and Alaskan Natives also experience disproportionately poor health outcomes due to heart disease, diabetes, lower respiratory disease, cancer, liver disease and cirrhosis of the liver, accidental injuries, assault, homicide and suicide. It’s almost as if packing human beings into marginal-quality reservations, substituting their traditional diets with poorer, cheap, processed commodity based belly-fillers, polluting the land around them, and locking them into poverty isn’t actually healthy.

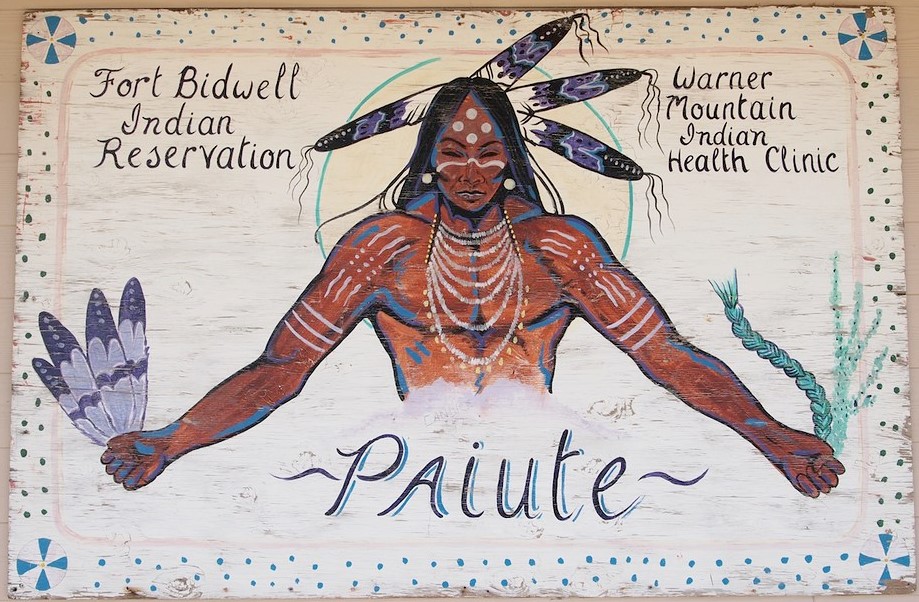

For her part, Roselyn Tso promised to “prioritize patient safety, worker retention, and technology upgrades at aging clinics and hospitals” and will serve as an advocate and voice for the health needs of Native people in the Biden administration. The IHS, as a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, has a 15,000-person staff with a $6.6 billion budget, including a $400 million increase that is barely expected to cover inflation for the 2.6 million Indigenous people served by the IHS (mostly at remote clinics on reservation land), much less than the transformational changes that the Biden campaign promised Native people. Tso has a lot of work to do, holding Team Biden to his word while lobbying Congress to earmark an appropriate, effective level of funding for the IHS. That would be $36.7 billion.

If that sounds like a lot of money, it is. However, Indigenous Americans have already paid for this and more, through land cession and loss of independence over the last few centuries. As an aside, a right-wing objection to student loan forgiveness making the rounds on social media is that if your degree hasn’t landed you a job sufficient to repay your education debt, then it’s not a good enough degree for your neighbor to pay off, either. True or not, perhaps a fair extrapolation is that if appropriating the vast majority of the continent yielded insufficient revenue to provide care and necessities in perpetuity for the descendants of those with whom our ancestors contracted the exchange of support for land, maybe it’s time to give that land back again.

Roselyn Tso joins Native American Biden administration appointees like Deb Haaland, Lynn Malerba, Ann Marie Bledsoe Downes, Heather Dawn Thompson, Elizabeth Carr, JoAnn Chase, Janie Simms Hipp, Natalie Landreth, Wahleah Johns and several others, bringing a wide array of backgrounds and ideas to bear on the governance of a diverse and divided country. While Biden’s commitment to diversity may be seen as merely cosmetic by a Left interested in more effective change and as virtue signaling by the Right’s outrage machine, many have waited for years to have even this much representation or hope for a better future.

Good luck, Roselyn, on the road ahead. Walk in beauty.

Related: Kimberly Teehee, First Cherokee Delegate

Join the conversation!