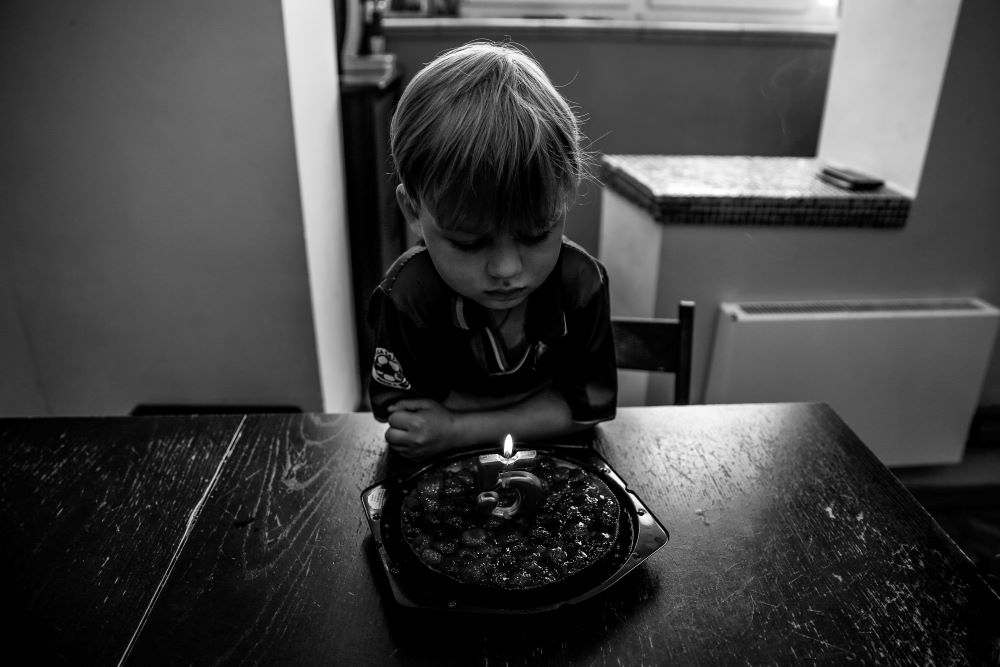

Childhood adversities linked to sex-specific health complications later in life.

A study by UCLA Health has revealed that childhood trauma can lead to sex-specific health risks later in life. While existing research already shows that early struggles can impact long-term physical and mental well-being, this study sheds new light on how different types of stressors influence biological functions, increasing health complications based specific on a person’s sex. The research, published in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, is one of the most thorough analyses on the subject to date.

Led by Dr. George Slavich, Director of the Laboratory for Stress Assessment and Research at UCLA, the team referenced existing data from more than 2,100 participants in the “Midlife in the United States” study, funded by the National Institute on Aging. Participants reported on their adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including financial hardship, abuse, neglect, frequent geographic relocations, and living apart from biological parents. They also provided biological samples that were used to measure 25 disease biomarkers, including those related to inflammation, metabolism, and stress. Participants disclosed whether they had been diagnosed with any of 20 major health conditions, allowing researchers to connect childhood trauma with biological and clinical outcomes in adulthood.

Analyzing the results, the team identified patterns among the participants, grouping them into stressor classes based on the number and severity of adversities they had experienced. For men, two distinct groups were created: high stress and low stress. For women, three groups were identified: high stress, moderate stress, and low stress. As anticipated, participants in the low-stress groups reported fewer major health issues, while those in the high-stress groups were more prone to health problems. However, the team then took these findings an important step further by examining sex-specific differences in how these stressors influenced outcomes.

Both men and women in the high-stress classes demonstrated poor metabolic health and higher inflammation levels. Still, women experienced a more significant impact on certain metabolic health biomarkers when compared to men, which could explain why women are often more vulnerable to diseases associated with inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, such as autoimmune disorders. On the other hand, men who experienced emotional abuse and neglect in childhood showed higher risks of blood disorders, mental health conditions, and thyroid problems.

Researchers cited the need for healthcare providers to assess childhood stress and trauma more often when children present for treatment. According to Dr. Slavich, many individuals who have suffered significant stress early in life never undergo any form of assessment for its impact on their physical health. This oversight can lead to missed opportunities for early intervention and prevention of future health issues.

By recognizing that the fact that biological consequences of early life adversity differ between men and women, clinicians can move away from a one-size-fits-all approach and adopt a more tailored approach to care. The study also highlights the growing recognition of stress as a key factor in the development of chronic illnesses. Stress has been implicated in nine out of the ten leading causes of death in the United States, yet it remains under-assessed in clinical settings. Dr. Slavich emphasizes that it is time to take this issue seriously and to spread awareness around the connection.

Sources:

UCLA study links childhood trauma to sex-specific health risks later in life

Join the conversation!