Both an ongoing lawsuit and an apparent major victory are making your right to repair your own equipment less likely to be enshrined in law.

If you buy something, you should own it. You should be able to use it, sell it, set it on fire if you want (local ordinances vary, of course) and you, or your favorite mechanic, should be able to fix it if it breaks. Unfortunately, your right to repair your own stuff is on shakier ground this week, due to an ongoing suit as well as an apparent victory.

Massachusetts passed laws in 2013 which explicitly gave consumers the right to fix their broken smartphones and cars. The auto repair law gave independent mechanics the same right to pull some diagnostic data from a car’s computer as the manufacturers originally granted only to franchise dealerships, but deliberately excluded telematics from the mandate. The world (especially some parts of it) is full to brimming with e-waste and Massachusetts rightfully decided that adding to the pile was unconscionable, and these laws were a step in the right direction.

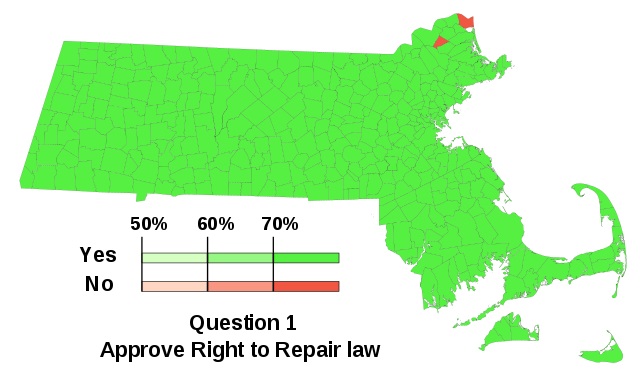

In 2020, voters there followed up by again overwhelmingly supporting a ballot measure requiring automakers to make vehicle telematics available to car owners and third party repair shops. These days, cars are giant computers with wheels and seats, so dependent upon chips to function that shortages during the pandemic’s supply chain snarl resulted in idled car factories. Telematics are the data points which highly computerized cars transmit back to the manufacturer, including the car’s overall health, mechanical problems, or basic maintenance needs, like whether the car needs an oil change. Without this data, independent mechanics are at a competitive disadvantage to franchise dealerships when it comes to diagnosing problems, leading to more expensive fixes or even premature vehicle replacement.

Unlike in 2013, which prompted automakers to agree to data sharing methods, the 2020 law has been the object of a drawn out lawsuit, Alliance for Automotive Innovation v. Maura Healey. Manufacturers claim that giving consumers access to telematics would enable them to more easily disable emissions control features or federal safety regulations, although both Subaru and Kia complied by making telematics unavailable to both dealership and independent mechanics, certainly one way of insuring that neither had more inside information than the other. However, is absolute secrecy the best way to ensure hack-free safety and cybersecurity, or is it simply a way to effectively limit your right to repair your own car?

Meanwhile, a similar long-running situation with John Deere has resolved, in a way.

For years, John Deere has resisted making their tractors user-reparable. It’s cute when Deere bricks tractors stolen by Russian occupiers in Ukraine, but much less amusing when it’s a farmer’s major investment in the means of production. Yet, Deere maintains that its ability to lock the equipment’s software and require an authorized dealer to unlock it is critical for preserving the company’s intellectual property and those same safety features and emissions controls that the auto manufacturers are worried about.

Farmers have been hacking their computerized Deeres on the sly in order to get their jobs done, but they might not have to anymore since Deere and the American Farm Bureau Federation lobbying group signed a non-legally-binding Memorandum of Understanding last week. The agreement allows farmers and third party mechanics to access diagnostic information, manuals and proper tools to repair the equipment, so long as it isn’t for the purpose of breaking laws or divulging Deere’s intellectual property, of course.

As helpful as this turnabout is for farmers incentivized by economic reality to keep their tractors running for as long as humanly possible in a country where are there are more than 12,000 farms for every single authorized Deere dealership, it is not an unalloyed good. Your right to repair your own tractor could be yanked out from under you if actual right-to repair laws start to gain, um, traction.

Just as Deere argued in 2018 that its proprietary, lockable software would make it unnecessary to pass legislation mandating certain repair-related regulations by “doing the work” of those laws directly and voluntarily, Deere is also claiming that this MoU should take the place of actual legislation aimed at enshrining your right to repair into law. However, to prevent the American Farm Bureau Federation’s members from “introducing, promoting or supporting” such legislation, Deere will back out of the MoU should state or federal right-to-repair laws be passed.

That’s a lot of trust to put in a company that hasn’t particularly made things easy for farmers over the years, and who frowns upon the right to petition the government for redress of grievances.

When you own something, you or your favorite mechanic should be able to fix it. The fact that it doesn’t necessarily happen that way isn’t merely inconvenient, it highlights the uncomfortably wide gulf between the power and influence of giant companies and the little folks like you and me.

Related: Right to Repair Gaining Ground

Join the conversation!